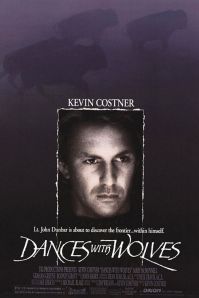

There are only a couple minutes of dancing in Kevin Costner’s three-hour film, so thank Kevin they’re good. The best scene in the movie is of Costner’s rogue hero, an American Civil War lieutenant named John Dunbar, dancing alone one night around a bonfire in front of his fort. His movements resemble those from a musical ceremony of the nearby Sioux Indians, with whom Dunbar is becoming friendly. The sight of a white man reveling this way in isolation is at once novel and primal. Its charge comes in part from the distance between Dunbar and familiar social order. He’s stationed at an outpost on the Western frontier, with ample supplies but little company. There’s his horse, a benevolent wolf that pads around, and eventually the Sioux, especially the sanctified Kicking Bird (Graham Greene) and the babelicious Stands With A Fist (Mary McDonnell).

There are only a couple minutes of dancing in Kevin Costner’s three-hour film, so thank Kevin they’re good. The best scene in the movie is of Costner’s rogue hero, an American Civil War lieutenant named John Dunbar, dancing alone one night around a bonfire in front of his fort. His movements resemble those from a musical ceremony of the nearby Sioux Indians, with whom Dunbar is becoming friendly. The sight of a white man reveling this way in isolation is at once novel and primal. Its charge comes in part from the distance between Dunbar and familiar social order. He’s stationed at an outpost on the Western frontier, with ample supplies but little company. There’s his horse, a benevolent wolf that pads around, and eventually the Sioux, especially the sanctified Kicking Bird (Graham Greene) and the babelicious Stands With A Fist (Mary McDonnell).

Such a scenario, haunted by the spirits of Snow White and Robinson Crusoe, is ripe for sentimentality. Dances with Wolves doesn’t push your buttons so much as pound them. The music announces events in advance, like the wash of strings and flute before the neighborly wolf eats out of Dunbar’s hand for the first time. The characters are either good or vile, with almost no exception. Dunbar and the Sioux occupy the first category; other white men and the Pawnee, bloodthirsty Sioux enemies, are damned to the other. Yet the movie has a passionate earnestness that allays the lack of subtlety. It invites you to abandon the constraints of American civilization for a dance around the bonfire of a Native American civilization.